Jane Burrell's story of courage, patriotism and sacrifice has become part of a larger story of sexism and the unfortunate power of those in power. Let's taking a look back to remember her and move forward in a wiser direction.

Jane was a housewife when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, but a housewife with a degree from Smith College. To join the war effort, she got work as a junior clerk in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the CIA.

Most women in the OSS spent the war as typists and clerks, but this daughter of a Dubuque, Iowa, newspaper editor and writer, became an American spy serving behind enemy lines in Europe.

This is the story of how Jane Burrell made her mark in counterintelligence helping turn Nazi spies and how her skill and success helped pave the way for women in the CIA.

A Woman Pioneer in Counterintelligence

Unfortunately, after Jane's incredible work as a WWII spy, her career ended tragically. In 1948, she became the first active officer to die in the postwar CIA. She was never officially honored because the government kept the true nature of her death secret.

CIA Officer Jane Wallis Burrell

Jane started in the Pictorial Records Section of OSS, processing photographs taken in Nazi-occupied Europe and developing intelligence. Creating detailed maps from the images helped the Allies identify targets and coordinate strategy for air and ground forces.

Below: Photo similar to those Jane worked with. It shows Aachen Merzbrück Airfield,

Aachen, Germany. US Army Photo.

The OSS quickly promoted Jane due to her proficiency in the French language. French had been her major college, plus she had studied a year abroad in France, and traveled in Italy, Spain and Germany.

In 1943, she was sent to London and eventually transferred into X-2, the OSS's elite unit of spies and communications officers where she worked in counterintelligence, (CI). The X-2 collected intelligence, identified enemy assassins and saboteurs, interrogates sources, and ran agents.

Jane Burnell in a London park in 1943.

Part of Operation Double Cross, Jane worked to turn German spies to the Allied side, in particular Carl Eitel, who gave up the name of another German agent in France, known as a Spaniard, Juan Frutos.

She and others on the team then turned Frutos in time to feed Germany misinformation before the June 1944, D-Day landing at Normandy. To gain the advantage of surprise, the Allies deployed life-size inflatable ships, tanks and aircraft in the waters around Brest, far south and west of the planned invasion. Double agents, including Frutos, aided in the deceit. His counter-spy intelligence later that year allowed Allies to avoid Nazi U-boats and reinforce Allied supply lines.

In 1945, Burrell's team turned two other German spies, George Spitz and Friedrich Schwend, who revealed Nazis had stored gold in a 15-century castle in the Italian Alps, a nest egg to finance officers' escape to South America if Germany lost the war.

At the end of war, spies were laid off. The OSS with its X-2 officers dissolved and succeeded by the Strategic Services Unit, which in turn gave way in October 1946 to the Central Intelligence Group. Then in 1947 that group became the Central Intelligence Agency we know today. Jane Burrell rode out all the changes becoming one of the first officers in the CIA.

It was 110 days later, an Air France DC-3 from Brussels crashed in thick fog on approach to the Le Bourget airport near Paris, killing all five crew members and 10 of the 11 passengers.

The official report following the fiery crash identified Jane and an American clerk or courier, and the CIA stated she was on vacation at the time.

A letter in the Smith College Archives written from Jane's father, James Harold Wallis, to college President Herbert Davis states “Jane had been doing really important work for our government, and was on an official mission at the time of the accident.”

A US Department of State document stating Burrell was "on official travel

when the accident occurred."

Today, on the walls of the CIA headquarters, 113 stars honor officers who were killed in action. There is none for Jane Burrell. The CIA claims there is limited documentation about Jane's activity at the time of her death and that she was “never a candidate for a star.”

“At the same time, her service with the CIA and its predecessor organizations was honorable and deserves to be remembered,” says the story on the agency’s website.

Under duress of war, men in government agencies recognized women's abilities and set aside their prejudice and sexist attitudes. And a few years later, female CIA officers saw their contributions devalued as "...a potent combination of misogyny and political arrogance was shunting aside the elegantly clandestine work of information gathering in favor of more brute force covert action."*

As the postwar intelligence force contracted, women's abilities became less valued. In 1953, women employees of the CIA complained to incoming director Allen W. Dulles. They were paid less than men and not given equal benefits.

The women denounced the agencies preference for the “pale, male and Yale.”

"Increased homogeneity lent a vulnerability to their operations," According to Nathalia Holt, author of Wise Gals: The Spies Who Built the CIA and Changed the Future of Espionage The lack of diversity, in both thought and outward appearance, weakened their missions–and even potentially made their officers easier to identify in the field."

Nathalia Hold reports this prejudice contributed to the horrific results of the Bay of Pigs incident in Cuba. An experienced officer woman officer and linguist was not allowed to actively gather intelligence, despite the shortage of men officers who spoke Spanish.

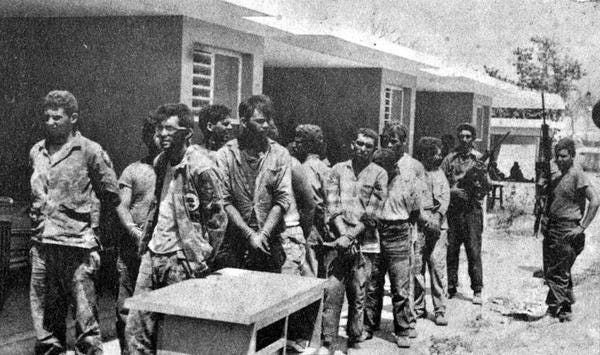

She was forced to listen helplessly as a covert attack, not supported by local intelligence in Cuba, failed. Some 1,500 Cuban exiles, trained and armed by the US to oust Fidel Castro ended up dead or in prison.

Cuban Exile Brigadistas captured after failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro, 1961.

There's a price to pay for devaluing the gifts of women, which rarely paid by those in power. CIA Director Dulles did listen to his female officers, in so much as he set up a group of women to investigate in 1953, which came to be called The Petticoat Panel: CIA's First Study - in 1953 - on the Role of Women in Intelligence.

The Petticoat Panel concluded “except for a few rather narrow fields, career opportunities for women have been limited in the Agency in nearly every professional area.”

The official response in January 1954? “...the status of women in the Agency does not call for urgent corrective action, but rather for considered and deliberate improvement primarily through the education of supervisors.”

Women and people of color had learned to beware considered and deliberate change. It usually means not change at all.

Sources

https://www.cia.gov/stories/story/the-petticoat-panel-role-of-women-in-intelligence/

https://www.criminalelement.com/book-review-wise-gals-by-nathalia-holt/

https://www.telegraphherald.com/news/features/article_961cb096-4e3c-11ed-bbb0-2379ba23d0f6.html'

https://thesophian.com/from-the-archives-the-legacy-of-jane-oneil-wallis-33/